Brown-Sequard Syndrome, as delineated in 1849 by Brown-Se´quard CE, emanates from trauma inflicted upon the anatomical hemicord. This trauma precipitates disruption of the descending lateral corticospinal tracts, the ascending dorsal columns (both of which decussate in the medulla), and the ascending lateral spinothalamic tracts, which intersect within one or two levels of the dorsal root entry. While total hemisection, evoking the hallmark clinical features of pure Brown-Sequard syndrome, is a rarity, incomplete hemisection resulting in Brown-Sequard syndrome accompanied by additional signs and symptoms is more prevalent. The clinical manifestation of this syndrome typically comprises ipsilateral spastic paralysis and impaired proprioception, tactile, and vibratory sensation, juxtaposed with contralateral deprivation of pain and thermal perception below the lesion site. Common etiologies encompass penetrating trauma, syringomyelia, hematomyelia, neoplasms, and blunt trauma, including atypical disk herniation (Oller DW, and Bone S. 1991). To date, the English language literature has documented 42 cases of Brown-Sequard syndrome attributed to cervical disc herniation, as outlined by Choi K B et al. (2009), Lee J K et al. (2007), Rustagi T et al. (2011), Wang C H et al. (2006), Yeung J et al. (2012), and Yokoyama K et al. (2012). Additionally, Kohno M et al. (1999) conducted a study revealing Brown-Sequard Syndrome in 16 individuals, comprising 7 with ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament, 5 with cervical spondylosis, and 4 with disc herniation, among a cohort of 233 surgically treated patients with cervical pathologies.

Brown-Sequard Syndrome stemming from blunt trauma is relatively infrequent. The pathogenesis of cord injury in cases of blunt trauma may entail vascular compromise, compression by bone or disk, or longitudinal tension on the cord, as highlighted by Oller DW and Bone S (1991), as well as Peacock WJ et al. (1997). The interplay of extension and flexion, along with rotation and the thrust technique, could potentially exert sufficient focused force to induce blunt injury limited to one side of the cord.

Cervical disc herniation presents a spectrum of management options, ranging from conservative measures such as medical treatment, physiotherapy, and rehabilitation, to surgical intervention, particularly in cases marked by progressive neurological decline or resistance to conservative approaches. Notably, the C5-C6 disc emerges as the most frequently implicated level, as observed by Abouhashem S et al. (2013).

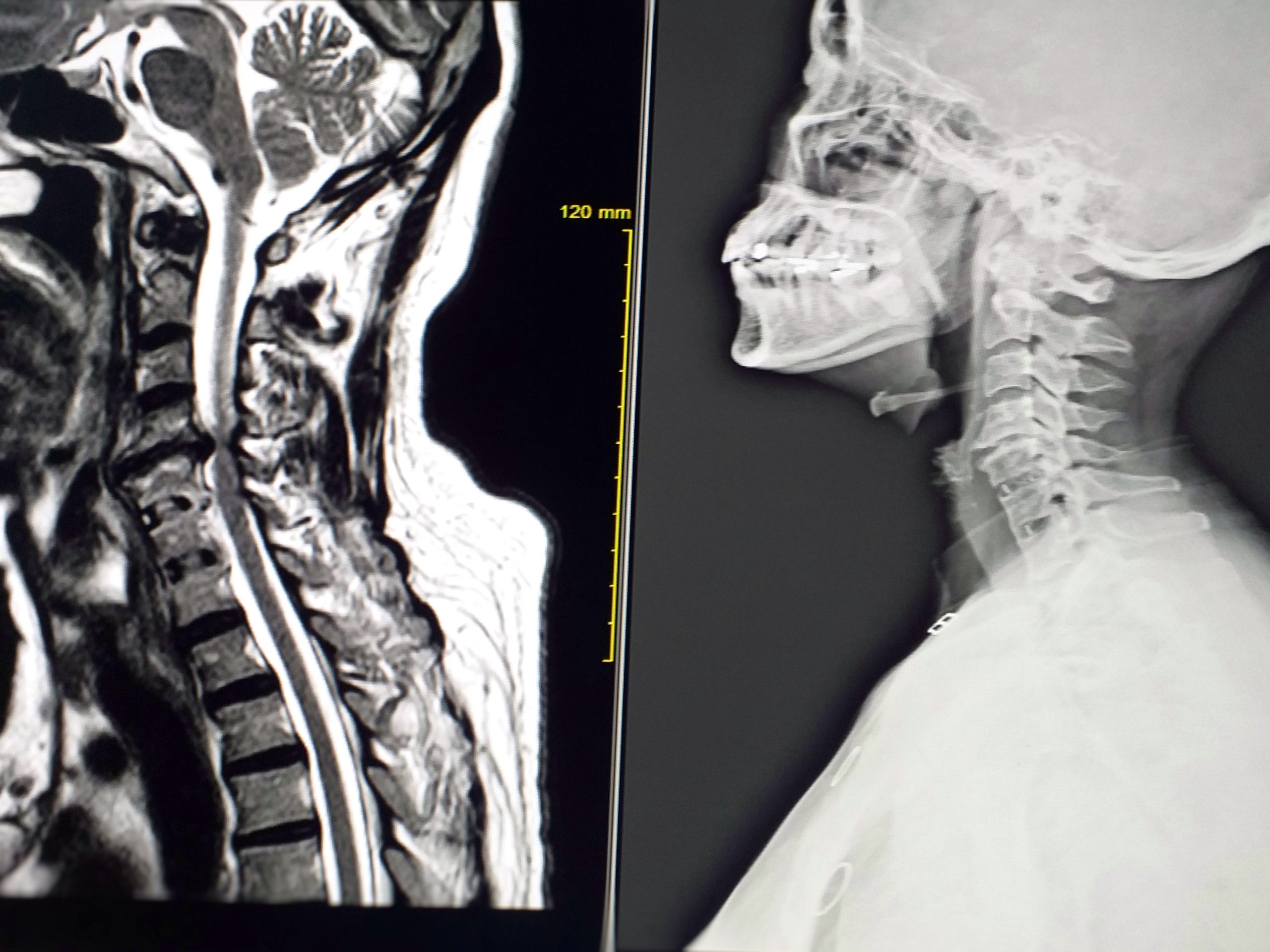

In cases where Brown-Sequard syndrome is preceded or accompanied by radicular signs and symptoms, the clinical history tends to be lengthier, averaging 7.2 months. Notably, intradural cervical disc herniations contributing to Brown-Sequard syndrome appear to correlate with a higher incidence of incomplete neurological recovery compared to classic extradural herniations. Strikingly, factors such as the presence of spinal cord hyperintensity on preoperative MRI, its persistence postoperatively, and the extent of spinal cord compression revealed by neuroradiological assessments do not significantly impact neurological recovery. Furthermore, the duration of clinical history does not exert influence on the ultimate outcome. The interval between symptom onset and diagnosis spans from 1 day to 18 months, with a mean of 4.9 months, as elucidated by Mastronardi L and Ruggeri A (2004).

Patients diagnosed with Brown-Sequard Syndrome may experience substantial motor recovery within a six-month timeframe, as delineated by Oller DW and Bone S (1991), Peacock WJ et al. (1997), and Little JW and Halar E (1985). Kohno M et al. (1999) further expound on this, revealing that individuals afflicted with Brown-Sequard Syndrome generally attain comparable functional outcomes to their non-Brown-Sequard counterparts, albeit with the notable exception of hemihypalgesia resolution, which typically persists unless the most rostral level of hemihypalgesia declines. These findings hold significance for educating preoperative patients. Moreover, Kohno M et al. (1999) elucidate several key insights:

- Among their cohort of 16 Brown-Sequard Syndrome patients, ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament in the central position emerged as the most prevalent disease and anterior element compressing the spinal cord configuration. Notably, severe spinal cord deformity tends to manifest in cases where the anterior element compressing the spinal cord is centrally located.

- Patients experiencing a reduction in hemihypalgesia levels exhibit notably superior recovery ratios compared to those with persistent hemihypalgesia.

- The laterality of the cord-compressing element, the extent of cord deformity, and the affected intervertebral levels demonstrate no discernible correlation with pre- and postoperative recovery ratios.

- Postoperative improvements in lower extremity motor function are significantly more pronounced in the disc herniation group compared to the ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament and cervical spondylosis cohorts.

In the realm of neurosurgery, the consideration of cervical disc herniation holds significant weight in diagnosing Brown-Sequard Syndrome (BSS), even when typical symptoms are absent. Cervical disc herniation poses a prevalent challenge, with patients presenting a spectrum of symptoms ranging from neck pain and cervical radiculopathy to myelopathy or radiculomyelopathy. While herniated discs commonly manifest symptoms on the ipsilateral side, as observed by Yeung J et al. (2012), rare occurrences exist wherein contralateral symptoms emerge, often manifesting as complete or incomplete Brown-Sequard syndrome.

This neurological syndrome stems from incomplete compression of the spinal cord, resulting in ipsilateral motor deficits, loss of proprioception and vibratory sensation, accompanied by contralateral impairment of pain and temperature perception, as elucidated by Choi K B et al. (2009), Kobayashi N et al. (2003), and Urrutia J and Fadic R (2012). Given the severity of this condition, early surgical intervention is advocated, as underscored by Mastronardi L and Ruggeri A (2004).

- Abouhashem S, Ammar M, Barakat M, Abdelhameed E. Management of Brown-Sequard syndrome in cervical disc diseases. Turk Neurosurg. 2013;23(4):470-5.

- Brown-Se´quard CE. De la transmission des impressions sensitives par la moelle epiniere. C R Soc Biol 1849:1:192–1194. Wilkins RH, Brody IA, eds. English Translation in Neurological Classics. New York: Johnson Reprint Corporation; 1973:49–50.

- Borm W and Bohnstedt T: Intradural cervical disc herniation. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg 92(2): 221-224, 2000.

- Choi K B, Lee DC, Chung DJ, Lee SH: Cervical disc herniation as a cause of Brown Sequard syndrome; J Korean Neurosurg Soc 46(5):505-510, 2009.

- Kobayashi N, Asamoto S, Doi H, Sugiyama H: Brown-Sèquard syndrome produced by cervical disc herniation: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Spine J 3(6):530-533, 2003.

- Kohno, M., Takahashi, H., Yamakawa, K., Ide, K., & Segawa, H. (1999). Postoperative prognosis of Brown-Séquard-type myelopathy in patients with cervical lesions. Surgical neurology, 51(3), 241–246.

- Lee J K, Kim YS, Kim SH: Brown–Sequard syndrome produced by cervical disc herniation with complete neurologic recovery: Report of three cases and review of the literature. Spinal Cord 45(11), 744–748, 2007.

- Little JW, Halar E. Temporal course of motor recovery after Brown-Se´quard spinal cord injuries. Paraplegia 1985;23:39–46.

- Mastronardi L, Ruggeri A. Cervical disc herniation producing Brown-Sequard syndrome: case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004 Jan 15;29(2):E28-31.

- Oller DW, Bone S. Blunt cervical spine Brown-Se´quard injury: a report of three cases. Am Surg 1991;57:361–365.

- Peacock WJ, Shrosbree RD, Key AG. A Review of 450 stabwounds of the spinal cord. S Afr Med J 1977;51:961–964.

- Rustagi T, Badve S, Maniar H, Parekh A: Cervical disc herniation causing brown-séquard’s syndrome: A case report and literature review. Case Reports in Orthopedics, 2011: 1-6, 2011.

- Urrutia J, Fadic R: Cervical disc herniation producing acute Brown-Sequard syndrome: Dynamic changes documented by intraoperative neuromonitoring. Eur Spine J 21(4): S418-421, 2012.

- Wang C H,Chen CC and Cho CD: Brown-Sequard syndrome caused by cervical disc herniation. Mid Taiwan J Med 11: 62-66, 2006.

- Yeung J, Johnson J, Karim A: Cervical disc herniation presenting with neck pain and contralateral symptoms: A case report. Journal of Medical Case Reports 6:166, 2012.

- Yokoyama K, Masahiro Kawanishi M, Yamada M, Kuroiwa T: Cervical disc herniation manifesting as a Brown-Sequard syndrome. J Neurosci Rural Pract 3(2):182–183, 2012.