The history of neck pain is explained in this blog. The distribution, natural history, and clinical course of a disease are all factors that contemporary clinical epidemiology considers. We present a quick summary of these dimensions in relation to neck pain.

Let’s discuss prevalence:

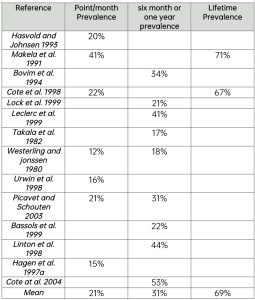

Compared to lumbar back pain, the epidemiology of neck pain in the adult population has received less attention, although there is still a sizable body of literature from which to draw. The variations in sampling techniques, response rates, and terminology among the researchers could account for some of the discrepancies in the findings. In two investigations, the lifetime prevalence of neck pain was almost 70%. According to a variety of studies, between 12% and 41% of the general population experience point, month, and year prevalence.

Table show prevelance of neck pain across the studies

These studies highlight the prevalence of these pain complaints in the general adult population, but they do not provide information on the severity, durability, or effects of neck discomfort on people’s daily lives.

Let’s discuss natural history:

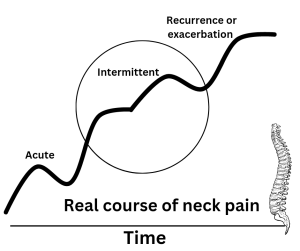

Neck pain typically has a lengthy and episodic natural history. Over 250 patients with neck pain participated in two long-term follow-ups, and nearly 60% of them reported ongoing or recurring issues (Lees and Turner 1963; Gore et al 1987). A third of cervical radiculopathy patients have reported at least one prior episode (Radhakrishnan et al. 1994). In a twelve-year follow-up study, only 4% of people who had been first hospitalised for neck pain reported being pain-free, while 44% said they were the same or worse off than they had been twelve years prior (Kjellman et al. 2001). Nearly 800 people who had previously reported neck pain participated in a follow-up study, and 48% of them still had symptoms after a year (Hill et al. 2004). According to all of these reports, at least 40% of people who experience neck pain have a history of relapse and subsequent episodes. Many months have passed, and some people with neck pain have reported having ongoing, persistent pain. The average of these numbers indicates that between 16% and 23% of adults in the general population experience persistent neck discomfort that lasts at least three months, depending on whether the definition of neck pain is inclusive or limited.

In a sample of more than a thousand people, 15% experienced a new onset of neck pain, and 70% reported chronic, recurrent, or worse neck pain at one year (Cote et al. 2004). Just over half of the participants had neck pain at baseline. It is obvious that neck pain has a natural history that is comparable to that of back pain and that it is frequently persistent or recurrent.

- For a conclusion

- Neck pain is so frequent that it may be considered “normal,” much like the common cold. A self-management strategy that fosters personal responsibility should be paired with resistance to the medicalization of a common experience.

- Neck pain commonly progresses in a way that is characterised by episodes, persistence, flare-ups, recurrences, and chronicity. This must be kept in mind during the clinical interaction; management must focus on long-term benefits rather than just temporary symptom relief.

- Management must provide patient self-management and accountability, and active interventions, such as physical activity, should be used to treat neck discomfort.

References:

- Bassols A, Bosch F, Campillo M, Canellas M, Banos JE (1999). An epidemiological comparison of pain complaints in the general population of Catalonia (Spain). Pain 83.9-16.

- Bovim G, Schrader H, Sand T (1994). Neck pain in the general population Spine 19.1307-1309.

- Cote P, CaSSidy JD, Carroll L (1998). The Saskatchewan health and back pain survey. The prevalence of neck pain and related disability in Saskatchewan adults. Spine 15.1689-1698.

- Cote P, Cassidy jD, Carroll LJ, Kristman V (2004). The annual incidence and course or neck pain in the general population: a population-based cohort study. Pain 112.267-273.

- Gore DR, Sepic SB, Gardner GM, Murray MP (1987). Neck pain: a long-term followup of 205 patients. Spine 12.1-5.

- Hagen KB, Kvien TK, Bjorndal A (1997a). Musculoskeletal pain and quality of life in patients with noninflammatory joint pain compared to rheumatoid arthritis: a population survey. j Rheumatol 24.1703-1709.

- Hasvold T, Johnsen R (1993). Headache and neck or shoulder pain – frequent and disabling complaints in the general population. Scand J Prim Health Care 11.219-224.

- Hill J, Lewis M, Papageorgiou AC, Dziedzic K, Croft P (2004). Predicting persistent neck pain. A I-year follow-up of a population cohort. Spine 29. 1648-1654.

- Kjellman G, Oberg B, Hensing G, Alexanderson (200 1). A 12-year follow-up of subjects initially sicklisted with neck/shoulder or low back diagnoses. Physio Research Int 6.52-63.

- Lees F, Turner JWA (1963) Natural history and prognosis of cervical spondylosis. BMJ 1607-1610.

- Leclerc A, Niedhammer I, Landre MF, Ozguler A, Etore P, Pietri-Taleb F (1999). Oneyear predictive factors for various aspects of neck disorders. Spine 24.1455- 1462.

- Linton Sj (1998). The socioeconomic impact of chronic back pain: is anyone benefiting? Pain 75.163-168.

- Lock C, Allgar V ,jones K, Marples G, Chandler C, Dawson P (1999). Prevalence of back, neck and shoulder problems in the inner City: implications for the provision of physiotherapy services in primary healthcare. Physio Res Int 4.161-168.

- Makela M, Heliovaara M, Sievers K, Impivaara 0, Knekt P, Aromaa A (1991). Prevalence, determinants, and consequences of chronic neck pain in Finland. Am J Epidemiology 134.1356-1 367.

- McKenzie RA (1981). The Lumbar Spine: Mechanical Diagnosis & Therapy. Spinal Publications, New Zealand.

- McKenzie RA (1983). Treat Your Own Neck. Spinal Publications, New Zealand.

- McKenzie RA (1990). The Cervical & Thoracic Spine: Mechanical Diagnosis & Therapy. Spinal Publications, New Zealand.

- McKenzie R, May S (2003) The Lumbar Spine: Mechanical Diagnosis & Therapy. Spinal Publications, New Zealand.

- Takala J, Sievers K, Klaukka T (1982). Rheumatic symptoms in the middle-aged population in south-western Finland. Scand J Rheum (Supp1) 47.15-29.

- Urwin M, Symmons D, Allison T et al. (1998). Estimating the burden of musculoskeletal disorders in the community: the comparative prevalence of symptoms at different anatomical sites, and the relation to social deprivation. Ann Rheum Dis 57.649-655.

- Westerling D, Jonsson BG (1980). Pain from the neck-shoulder region and sick leave. Scand J Soc Med 8.131-136.