There is no agreement on a definition or diagnostic criteria for “sciatica.” The term “sciatica” has been used to describe a variety of nerve-related disorders originating in the spine, including radicular discomfort and painful radiculopathy (Foster NE, et al., 2020; Lin CW, et al., 2014). Despite the linguistic connotation of neural involvement, the term “sciatica” has been used to refer to somatic-referred pain in some cases (Lin CW et al. 2014). The inconsistent use of terminology for the diagnostic labels, “sciatica” or radicular pain or painful radiculopathy, and the identification of neuropathic pain are two of the key issues involved with a diagnosis of “sciatica.” These obstacles impede collective clinical and scientific understanding and clarity about these conditions, have an impact on effective clinical communication and care planning, prevent clear interpretation of the scientific literature related to the condition, and may ultimately contribute to the limited efficacy of care for people living with “sciatica.” Indeed, most trials on conservative management for people with “sciatica” either show no, or at best, modest effects (Dove L, et al., 2023; Hahne AJ, et al., 2010; Jacobs WC, et al., 2011; Jesson T, et al., 2020; Lewis RA, et al., 2015; Luijsterburg PA, et al., 2007; Markman JD, 2018; Mathieson S, et al., 2019; Pinto RZ, 2017).

Let’s go in depth with each definition!

The “sciatica” conundrum:

setting the scene

The term “sciatica” is inaccurate and does not always help sufferers make sense of their discomfort.

Spine-related leg discomfort is described using a variety of terminology. “Sciatica” is the most widely used term (Lin CW et al. 2014). According to the Concise Oxford Medical Dictionary, “sciatica” is “pain radiating from the buttock into the thigh, calf, and occasionally the foot.” This definition is immediately followed by the caveat that “although it is in the distribution of the sciatic nerve, sciatica is rarely due to disease of this nerve.” This disclaimer emphasises the debate about the term “sciatica.” For many years, it has been maintained that the term “sciatica” is obsolete (Fairbank JC. 2007; IASP. 2012). The wide range of prevalence estimates published for “sciatica” (1.6%–43%) is most likely due to a lack of agreement on terminology and case definition (Konstantinou K. and Dunn KM. 2008).

Importantly, the heterogeneity of patient populations caused by inconsistent terminology (including case definitions) and variable eligibility criteria may explain some of the conflicting evidence and influence the interpretation of the efficacy of treatments (for example, physiotherapeutic interventions and pharmaceutical management) for people with “sciatica.” (Dove L., et al., 2023; Enke O., et al., 2018; Jesson T., et al., 2020; Lin CW, et al., 2014; Mathieson S., et al., 2019; Pinto RZ, 2017). As a result, the IASP has proposed that the term “sciatica” be avoided (IASP, 1994). Instead, they advised that pain in the lower limb originating from the lower back be characterised using more specific case definitions such as referred pain, radicular pain, or (painful) radiculopathy (IASP, 2012). These definitions are consistent with Bogduk N.’s (2009) terminology.

Case definitions for particular spine-related leg pain

It is recommended to employ case definitions for specific spine-related leg pain, such as the ones listed below (Bogduk N. 2009; IASP. 2012):

- Somatic-referred pain

- Radicular pain without or with radiculopathy

1. Somatic-referred pain:

generated by noxious nerve stimulation of somatic tissues but felt in regions innervated by nerves other than those innervating the site of noxious stimulation (Bogduk N. 2009; IASP. 2012). Tendons, ligaments, fascia, and bones were also mentioned as probable origins of somatic-referred pain in the context of spine-related leg discomfort. These regions are indeed nociceptively innervated (Bailey JF, et al., 2011; Benditz A, et al., 2019; Mense S., 2019) and can generate referral patterns into the lower limb (Feinstein B, et al., 1954; Kellgren JH., 1939).

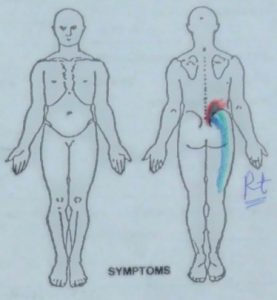

Pain might be dull, agonising, gnawing, or pressure-like. Although somatic referred pain is most commonly found in the gluteal and thigh areas, it can also occur in the lower leg and, in rare cases, the foot (Feinstein B. et al., 1954; Kellgren JH., 1939). Somatic referred pain must be separated from visceral referred pain, which may also refer to the limbs, notably the gluteal or groyne areas in the lower limbs (Head H. 1893). A detailed clinical history will be necessary for this patient to determine the nature of the focal and referred pain.

Identifying people who have somatic-referred leg pain

Individuals with only somatic referred leg pain have no neurological signs or symptoms (Bogduk, 2009; Fukui et al., 1997; O’Neill et al., 2002); hence, neurological integrity tests (light touch, reflex testing, and muscular strength) will be normal. Furthermore, neurodynamic studies employing structural differentiation (Coppieters et al., 2005; Nee et al., 2012a) would be negative since the nerve in these individuals is not inflamed (Bogduk, 2009; Fukui et al., 1997; O’Neill et al., 2002). Individuals with somatic referred pain can be identified in addition to negative findings in the tests described by reproducing their pain with movements that load the local soft tissues around the lumbar spine, such as active range of motion (AROM) and passive accessory intervertebral movements (PAIVMS) of the lumbar spine, or manual testing of the muscles around the spine (Petty, 2011a; Refshauge and Gass, 2004). If an individual’s symptoms are recreated by at least one physical test method of a spinal nonneural structure (and they have negative neurological integrity and neurodynamic tests), they may have somatic referred pain.

2. Radicular pain without radiculopathy:

Radicular pain is most likely caused by hyperexcitability and ectopic dorsal root or dorsal root ganglia discharges. This could be due to inflammatory irritation, ischaemia, or mechanical deformation of brain structures, or a combination of these and their downstream mechanisms (e.g., inflammation) (Schmid AB, 2015; Schmid AB, 2020).

The pain is described as startling, lancinating, electric, stabbing, or shooting, and it is frequently accompanied by a dull background aching (Murphy DR, et al. 2009; Smyth MJ, and Wright V. 1958). Sharp and scorching were also added as potential pain descriptors because they are frequently reported by individuals with lumbar radicular pain (Murphy DR, et al. 2009). Radicular discomfort can be either spontaneous or induced, for example, by particular spinal or leg motions.

Patients may suffer paraesthesia and dysaesthesia, such as tingling, a “woollen feeling,” or “a block of ice,” in addition to pain. The pain can be deep or superficial, and it can radiate into the leg in places that are similar to, but not identical to, dermatomes (Murphy DR, et al. 2009). The working group also resolved to drop the earlier description of the pain’s “band-like” location (Bogduk N. 2009; IASP. 2012), which appeared to be adequately covered by “areas reminiscent of, but not necessarily identical to, dermatomes.”

Identifying individuals with Radicular pain:

Sensitised nerves will experience discomfort when moved (Hall and Elvey, 2004; Walsh and Hall, 2009b). Nerves must not only mechanically adapt to huge variations in nerve bed length but also physiologically because they must continue to function throughout such motions (Butler, 2000; Shacklock, 2005a). When the nerve becomes sensitive to movement, it indicates a compromise in its ability to cope mechanically or physiologically (Boyd et al., 2005; Gallant, 1998).

SLR and slump tests are two neurodynamic tests that affect the lumbosacral nerve roots, plexus, and continuations into the sciatic nerve and its divisions. The slump test stresses the more proximal sections of the neuraxis by producing more spinal cord and brain stem excursion (Butler, 2000; Shacklock, 2005a). One study found significant agreement (=0.69) and good reliability of both measures in people with spinally referred leg pain (r = 0.64) (Walsh and Hall, 2009c). Beith et al. (2011) discovered a statistically significant decrease in SLR range in patients with neuropathic back and leg pain versus those with nociceptive back and leg pain. Structural differentiation is an important part of neurodynamic testing to determine the presence of a mechanosensitive neuron. Structural differentiation consists of movements of the joints furthest distant from the site of symptoms, such that any change in symptoms is unlikely to be due to the local non-neural structures, which have not been moved.

As a result, it can be concluded that the SLR, or slump test, would detect pain caused by nerve root dysfunction. Furthermore, it has been proven that sensitised nerves are sensitive to touch as well as movement, and this sensitivity is typically felt along the course of the nerve trunk (Asbury and Fields, 1984; Walsh and Hall, 2009c).

Tenderness to palpation is likely to be felt along the path of the sciatic nerve in the case of lower lumbar spinal nerve roots, or DRG (Dyck, 1987; Walsh and Hall, 2009c). The use of nerve trunk palpation has been recommended (Schäfer et al., 2009, 2011; Walsh and Hall, 2009c). If two or more palpation sites were positive, the validity of palpation was good (sensitivity 0.83, specificity 0.73) when compared to slump tests or SLR (Walsh and Hall, 2009c).

To summarise, radicular pain can be detected by a positive SLR or slump test, as well as the presence of two or more painful spots on nerve palpation at the sciatic (buttock), tibial (behind the knee), and common peroneal (around the fibular head) nerves. However, because the sensitivity and specificity of nerve palpation were not 100% when compared to the SLR or slump test, a negative nerve palpation test might be observed in the presence of a positive SLR or slump test, and vice versa.

3. Radicular pain with radiculopathy:

Radicular discomfort can occur alongside radiculopathy (IASP, 2012). Radiculopathy is caused by a nerve root or dorsal root ganglion lesion or illness. Radiculopathy is clinically defined by neurological abnormalities (for example, dermatomal hypoesthesia or anaesthesia, myotomal weakness, or diminished or absent reflexes) that may or may not coexist with pain. These neurological disorders are induced by the slowing or blocking of small or large nerve fibres, or by true axotomy.

Whereas real neurological abnormalities are usually constant, fluctuations with postural changes, for example, have been observed (Sabbahi MA and Ovak-Bittar F. 2018). Such fluctuations may be due to an ischemic conduction block rather than a demyelinating conduction block. Although painless radiculopathy does exist (for example, pure motor radiculopathy or mixed sensory and motor radiculopathy without pain), radiculopathy can also occur in conjunction with radicular discomfort, which is referred to as painful radiculopathy (IASP, 2012). People with radiculopathy may occasionally experience somatic-referred pain (IASP, 2012).

As a result, we can conclude that neurological integrity tests are essential to distinguishing radicular discomfort from radiculopathy. Individuals with negative neurological integrity, neurodynamic tests, or nerve palpation may be diagnosed with somatic referred leg pain; however, additional testing is required to ensure that the pain is neuromusculoskeletal in origin and related to the spine rather than other local structures such as the hip joint.

Identifying individuals with Radiculopathy:

The clinical picture (e.g., history of the condition, localization of symptoms into the leg that are increased by spinal movements) and the existence of positive neurological bedside integrity tests should be used to decide if an individual should be classified as having radiculopathy.

A suggestion for an umbrella name that encompasses these three unique case definitions

(A. B. Schmidt et al., 2023)

It would be advantageous to have an umbrella phrase that encompasses these three unique case definitions. This was thought to be relevant for clinical purposes in distinguishing limb symptoms caused by structures in the back from those caused by nonspinal structures. Unlike sciatica, which refers to neurological issues, this word should include all three case definitions of somatic-referred pain, radicular pain, and painful radiculopathy.

Spine-related leg pain is a catch-all phrase for both nerve-related [e.g., radicular pain and painful radiculopathy] and somatic-referred pain. As a result, this term encompasses a larger range of symptoms than “sciatica,” which linguistically alludes to neurological involvement.

Spine-related leg pain has the advantage of being applicable to cervical diseases (ie, spine-related arm pain). Furthermore, spine-related leg pain was thought to be more specific, but back-related leg pain could be caused by disorders other than the spine, such as sacroiliac joint difficulties or piriformis syndrome.

References

- Asbury, A., Fields, H. 1984. Pain due to peripheral nerve damage: an hypothesis. Neurology 34: 1587-1590.

- Bailey JF, Liebenberg E, Degmetich S, Lotz JC. Innervation patterns of PGP 9.5-positive nerve fibers within the human lumbar vertebra. J Anat 2011;218:263–70.

- Benditz A, Sprenger S, Rauch L, Weber M, Grifka J, Straub RH. Increased pain and sensory hyperinnervation of the ligamentum flavum in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis. J Orthop Res 2019;37:737–43.

- Beith, I., Kemp, A., Kenyon, J., Prout, M, Chestnut, T.J. 2011 Identifying neuropathic back and leg pain: a cross-sectional study. Pain 152(7): 1511-6.

- Bogduk N. On the definitions and physiology of back pain, referred pain, and radicular pain. PAIN 2009;147:17–19.

- Butler, D. 2000. The Sensitive Nervous System Melbourne: NOI Press.

- Boyd, B. S., Puttlitz, C., Jerylin, G., Topp, K. S. 2005. Strain and excursion in the rat sciatic nerve during a modified straight leg raise are altered after traumatic nerve injury. Journal of Orthopaedic Research 23: 764-770.

- Coppieters, M. W., Kurz, K., Mortensen, T. E., Richards, N. L., Skaret, I. A., McLaughlin, L. M., Hodges, P. W. 2005. The impact of neurodynamic testing on the perception of experimentally induced muscle pain. Manual Therapy 10: 52-60.

- Dove L, Jones G, Kelsey LA, Cairns MC, Schmid AB. How effective are physiotherapy interventions in treating people with sciatica? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Spine J 2023;32:517-33.

- Dyck, P. 1987. Sciatic pain, In Lumbar discectomy and laminectomy. , R. G. Watkins, and J. S. Collins, eds. Aspen: Rockville, pp. 5-14.

- Enke O, New HA, New CH, Mathieson S, McLachlan AJ, Latimer J, Maher CG, Lin CC. Anticonvulsants in the treatment of low back pain and lumbar radicular pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 2018;190:E786–93.

- Fairbank JC. Sciatic: an archaic term. BMJ 2007;335:112.

- Feinstein B, Langton JN, Jameson RM, Schiller F. Experiments on pain referred from deep somatic tissues. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1954;36-A: 981–97.

- Foster NE, Konstantinou K, Lewis M, Ogollah R, Saunders B, Kigozi J, Jowett S, Bartlam B, Artus M, Hill JC, Hughes G, Mallen CD, Hay EM, van der Windt DA, Robinson M, Dunn KM. Stratified versus usual care for the management of primary care patients with sciatica: the SCOPiC RCT. Health Technol Assess 2020;24:1–130.

- Fukui, S., Ohseto, K., Shiotani, M., Ohno, K., Karasawa, H., Naganuma, Y. 1997 Distribution of Referred Pain from the Lumbar Zygapophyseal Joints and Dorsal Rami. Clinical Journal of Pain. 13(4): 303-307.

- Gallant, S. 1998. Assessing adverse neural tension in athletes. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation 7: 128-139.

- Hahne AJ, Ford JJ, McMeeken JM. Conservative management of lumbar disc herniation with associated radiculopathy: a systematic review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35:E488–504.

- Hall, T. M., Elvey, R. 2004. Management of mechanosensitivity of the nervous system in spinal pain syndromes, In Grieve’s Modern Manual Therapy, J. D. Boyling, G. A. Jull, eds. Churchill Livingstone.

- Head H. On disturbances of sensation with especial reference to the pain of visceral disease. Brain 1893;16:1–133.

- IASP. Classification of chronic pain. Seattle, WA: IASP Press, 1994.

- IASP. Classification of chronic pain. Seattle, WA: IASP Press, 2012.

- Jacobs WC, van Tulder M, Arts M, Rubinstein SM, van Middelkoop M, Ostelo R, Verhagen A, Koes B, Peul WC. Surgery versus conservative management of sciatica due to a lumbar herniated disc: a systematic review. Eur Spine J 2011;20:513–22.

- Jesson T, Runge N, Schmid AB. Physiotherapy for people with painful peripheral neuropathies: a narrative review of its efficacy and safety. Pain Rep 2020;5:e834.

- Kellgren JH. On the distribution of pain arising from deep somatic structures with charts of segmental pain areas. Clin Sci 1939;4:35–46.

- Konstantinou K, Dunn KM. Sciatica: review of epidemiological studies and prevalence estimates. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33:2464–72.

- Lewis RA, Williams NH, Sutton AJ, Burton K, Din NU, Matar HE, Hendry M, Phillips CJ, Nafees S, Fitzsimmons D, Rickard I, Wilkinson C. Comparative clinical effectiveness of management strategies for sciatica: systematic review and network meta-analyses. Spine J 2015;15:1461–77.

- Lin CW, Verwoerd AJ, Maher CG, Verhagen AP, Pinto RZ, Luijsterburg PA, Hancock MJ. How is radiating leg pain defined in randomized controlled trials of conservative treatments in primary care? A systematic review. Eur J Pain 2014;18:455–64.

- Luijsterburg PA, Verhagen AP, Ostelo RW, van Os TA, Peul WC, Koes BW. Effectiveness of conservative treatments for the lumbosacral radicular syndrome: a systematic review. Eur Spine J 2007;16:881–99.

- Markman JD, Baron R, Gewandter JS. Why are there no drugs indicated for sciatica, the most common chronic neuropathic syndrome of all? Drug Discov Today 2018;23:1904–9.

- Mathieson S, Kasch R, Maher CG, Zambelli Pinto R, McLachlan AJ, Koes BW, Lin CC. Combination drug therapy for the management of low back pain and sciatica: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain 2019;20:1–15.

- Mense S. Innervation of the thoracolumbar fascia. Eur J Transl Myol 2019;29:8297.

- Murphy DR, Hurwitz EL, Gerrard JK, Clary R. Pain patterns and descriptions in patients with radicular pain: does the pain necessarily follow a specific dermatome? Chiropr Osteopat 2009;17.

- Nee, R.J., Jull, G.A., Vincenzino, B., Coppieters, M.W. 2012a The validity of upper limb neurodynamic tests for detecting peripheral neuropathic pain. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy 42(5):413-424.

- O’Neill, C.W., Kurgansky, ME, Derby, R., Ryan, D.P. 2002. Disc stimulation and patterns of referred pain. Spine 27(24): 2776–2781.

- Petty, N.J. 2011a. Neuromusculoskeletal Examination and Assessment: A Handbook for Therapists. London: Churchill Livingstone 4th edition.

- Pinto RZ, Verwoerd AJH, Koes BW. Which pain medications are effective for sciatica (radicular leg pain)? BMJ 2017;359:j4248.

- Refshauge, K. Gass, E. 2004 Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy: Clinical Science and Evidence Based Practice 2nd edition Melbourne: Butterworth Heinemann.

- Sabbahi MA, Ovak-Bittar F. Electrodiagnosis-based management of patients with radiculopathy: the concept and application involving a patient with a large lumbosacral disc herniation. Clin Neurophysiol Pract 2018;3:141–7.

- Schäfer, A., Hall, T. M., Ludtke, K., Mallwitz, J., Briffa, N. K. 2009. Interrater reliability of a new classification system for patients with neural low back-related leg pain. Journal of Manual and Manipulative Therapy 17: 109-117.

- Schmid AB. The peripheral nervous system and its compromise in entrapment neuropathies. In: Jull G, Moore A, Falla D, Lewis J, McCarthy C, Sterling M, editors. Grieve’s modern musculoskeletal physiotherapy. 4th ed, 2015. p. 78–92.

- Schmid AB, Fundaun J, Tampin B. Entrapment neuropathies: a contemporary approach to pathophysiology, clinical assessment, and management. Pain Rep 2020;5:e829.

- Schmid, A. B., Tampin, B., Baron, R., Finnerup, N. B., Hansson, P., Hietaharju, A., Konstantinou, K., Lin, C. C., Markman, J., Price, C., Smith, B. H., & Slater, H. (2023). Recommendations for terminology and the identification of neuropathic pain in people with spine-related leg pain. Outcomes from the NeuPSIG working group. Pain, 164(8), 1693–1704.

- Shacklock, M. 2005a. Clinical Neurodynamics: A New System of Musculoskeletal treatment Philadelphia: Elsevier.

- Smyth MJ, Wright V. Sciatica and the intervertebral disc: an experimental study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1958;40A:1401–8.

- Walsh, J. Hall, T. 2009b. Agreement and correlation between the straight leg raise and slump tests in subjects with leg pain. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 32:184-192.

- Walsh, J., Hall, T. 2009c. Reliability, validity and diagnostic accuracy of palpation of the sciatic, tibial and common peroneal nerves in the examination of low back related leg pain. Manual Therapy 14: 623-629.