The McKenzie technique of mechanical diagnosis and therapy is a one-of-a-kind diagnostic and management approach. Robin McKenzie described the procedure first for lumbar spine disorders [McKenzie RA. 1981] and later for cervical and thoracic problems [McKenzie RA. 1990]. The approach uses repetitive motions while monitoring symptomatic and mechanical reactions as the primary source of information in the physical examination and then uses these responses to classify patients into mechanical subgroups. The management technique is determined by the subgroups, which are characterised as derangement, dysfunction, or postural conditions. Patients who do not meet the operational definitions for these syndromes can be classified as having one of the ‘other’ syndromes.

Mechanical diagnosis and therapy are more than simply a management system; they are also an assessment and classification system. The history portion of the assessment follows the standard format, which includes questions about the patient, their problem, its location, whether symptoms are constant or intermittent, the history of the problem, what causes symptoms to improve or worsen, any previous problems or treatments, medication history, and questions about Red Flags.

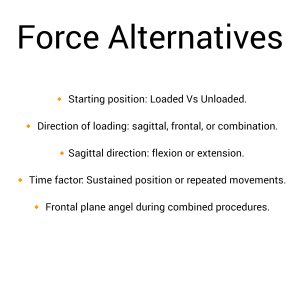

The physical examination for lumbar spine problems begins with an examination of posture, specifically the effect of posture correction on symptoms. If necessary, a neurological examination would be performed as part of the baseline assessment. Individual flexion, extension, and side-gliding motions are assessed, and any pain is reported. The therapist reassesses the baseline parameters from the history and physical examination to determine the response to management. The use of repeated motions is an important aspect of the physical examination. A variety of repeated movements could be chosen, including flexion while standing or lying, extension while standing or lying, and side-gliding while standing. However, not all of these motions would be checked in a single session; clinical decision-making by the therapist dictates which movements are examined. In general, sagittal movements will be prioritised because the majority of responses, particularly extension, occur in this plane. A patient with an acute-onset lateral deformity, on the other hand, would be treated first. Sets of roughly ten repeated motions can be repeated four or five times to determine the response before moving on to the next movement.

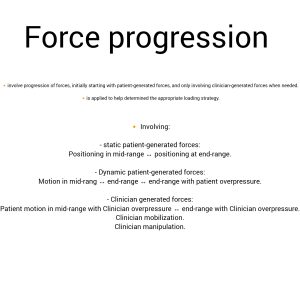

Before the repeated motions begin, the state of the patient’s symptoms, particularly the most distal, is noted. The patient’s symptoms are checked again after each round of repeated motions. To characterise the symptom response, a number of phrases are employed both during and after the motions. The mechanical diagnosis and therapy assessment are initially based solely on patient exercises; however, both the assessment and the management process allow for force progressions, which occur in the following order: patient forces early through end-range, patient forces end-range with patient overpressure, patient forces with therapist overpressure, and therapist mobilisation. As previously stated, overpressure is only used if the initial patient-generated forces are insufficient to create a meaningful reaction.

Prior to escalating forces, the therapist may choose to test patient overpressure over a 24- to 48-hour assessment period. The initial mechanical diagnosis and therapy assessment are typically performed standing, although force alternatives include repetitive laying motions and frontal plane movements with sidegliding or rotation.

Prior to escalating forces, the therapist may choose to test patient overpressure over a 24- to 48-hour assessment period. The initial mechanical diagnosis and therapy assessment are typically performed standing, although force alternatives include repetitive laying motions and frontal plane movements with sidegliding or rotation.

The management is determined by the classification; the patient is given one activity to undertake on a regular basis, with clear reasons for why they need to do that exercise or make that change to their posture; and management is particularly patient-centred.

The management is determined by the classification; the patient is given one activity to undertake on a regular basis, with clear reasons for why they need to do that exercise or make that change to their posture; and management is particularly patient-centred.

The therapist serves as an assessor and advisor, while the patient is the primary player in their recovery. The therapist provides them with a proper exercise, which serves as the mechanical treatment component, as well as clear reasons for the exercise, which serves as the educational component.

Finally, not every patient fits into one of the mechanical syndromes, and the ability to classify patients reflects a therapist’s expertise and training in the approach.

References

- McKenzie RA. The Lumbar Spine Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy. New Zealand: Spinal Publications; 1981.

- McKenzie RA. The Cervical and Thoracic Spine Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy. New Zealand: Spinal Publications; 1990.