In order to distinguish between an extremity source and a spinal source of symptoms, clinicians analyze the patient’s medical history and physical exam. When spinal pain is misdiagnosed as an issue with an extremity, it can lead to a series of bad decisions and ineffective treatment (Gunn C and Milbrandt WE 1976, Hashimoto S et al. 2019, Pheasant S 2016, Walker T et al. 2018).

The theory behind extremity pain of spinal origin is based on Hilton’s Law, which states that any nerve that supplies muscles extending across a joint not only innervates the muscle but also the joint and the skin overlying the muscle. For example, the quadriceps muscles are innervated by the femoral nerve (L4), which also provides sensory branches to the knee joint. Additionally, the sciatic nerve (L5 and S1) supplies the hamstrings with sensory branches that travel posteriorly to the knee.

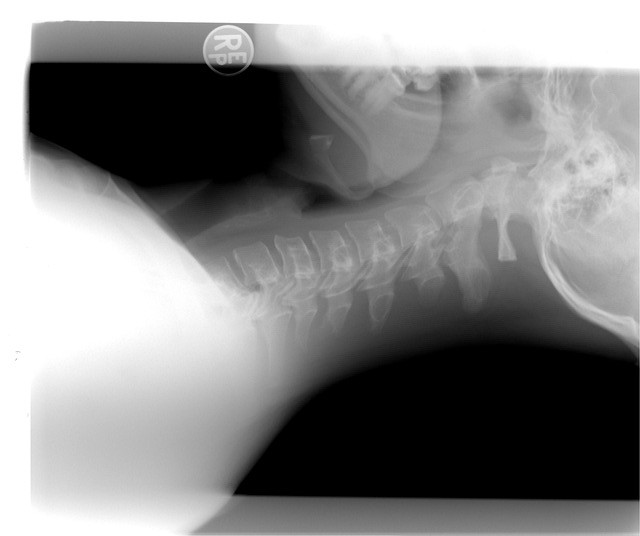

Mechanically reducible discogenic derangement: The most prevalent Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy (MDT) classification for pain originating from the spine and referring to an extremity is radicular pain, with or without radiculopathy (Hashimoto et al., 2019). Patients with herniated discs in the foraminal or extraforaminal regions may experience atypical symptoms (Friss et al., 1977; Jang et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2006). Importantly, these patients may exhibit a directional preference, meaning that repeatedly moving in a specific direction provides long-lasting clinical and functional improvement (Hashimoto et al., 2019; Heidar Abady et al., 2017; May and Rosedale, 2019). The validation of this directional preference was supported by a study conducted by Badghish et al. in 2015, which utilized the soleus H-reflex.

In a clinical setting, the initial MDT classification was either confirmed or rejected during follow-up visits, and treatment was either continued or changed in response to the results of the reassessment. Depending on the results of the reassessment, the treatment plan would either be continued or modified accordingly. If the patient’s primary complaint of extremity pain can only be treated with spinal therapy, it would be assumed that the pain originated from the spine. In other words, if the extremity symptoms can only be resolved through spinal mobilization or manipulation, the source of the discomfort can be assumed to be spinal.

Let’s discuss the prevalence: According to Rosedale R, et al 2020’s study, out of 322 individuals, 43.5% of all symptoms from the extremities had a spinal cause.

Instead of the typical radicular pain along a sensory dermatome, lumbar disc herniations may result in localized pain in the lower extremities (Wisneski RJ et al., 1999). The most common complaints involve thigh, calf, knee, ankle, or heel pain. In this study:

In this study, 39.4% of lower extremity pain cases overall had spinal origins:

- Hip pain accounted for 71% of all lower extremity pain with a spinal cause or 39.4% overall.

- Leg/thigh pain = 72.2%.

- Knee pain = 25.6%. [Moreover, 45% of osteoarthritic knees in a 2019 investigation of the knee by Hashimoto S et al revealed a spinal cause of symptoms.]

- Foot/ankle pain = 29 .2%.

48.3% of the subjects were reported to have a spinal source for their upper extremity pain:

- Shoulder pain = 47.6%; with additional investigations, a frequency between 10% and 27% was found (Karel YHJM et al 2017, Cannon DE et al 2007, Heidar Abady A et al 2017).

- Arm/forearm pain = 83.3%.

- Elbow pain = 44%.

- Hand/wrist pain = 38.5%.

According to Rosedale R. et al.’s study, a significant portion of extremity presentations had symptoms that were identified as having a spinal source and responded to spinal intervention. A “baseline-test-recheck baseline” method that is symptomatically driven offers a great deal of potential for revealing an unidentified source of extremity symptoms.

Let’s discuss indicators: The high prevalence reported by Rosedale R, et al. 2020 (43.5%) suggests that clinicians should thoroughly assess patients with extremity pain so they can decide on the best course of treatment.

The process of setting up reliable baseline assessments is a crucial component of the MDT examination. Symptomatic response and a review of baseline movements and activities should be done after each set of repetitive movements in order to gauge their impact. If the repetitive spinal movements had no impact on the baseline assessments, the extremity should then be investigated.

Five significant clinical indicators were linked to a spinal source in a study by Rastogi R, et al. in 2022. These were:

- Paresthesia is present.

- Symptoms alter when still, twisting the neck, or sitting.

- Symptoms change as the position changes.

- Limitation of spinal motion.

- No restrictions on the movement of the extremities.

Two out of the five indicators mentioned above can be used to predict the classification, with a sensitivity and specificity of 0.638 and 0.807 respectively. The high specificity (0.807) in the presence of two indicators points to a significant likelihood that the pain is coming from the spinal column. The moderate sensitivity (0.638) indicates that a patient with fewer than two indicators may not always be experiencing pain in their extremities.

These five indicators may enable clinicians to supplement their decision-making process with regard to spinal and extremity differentiation to appropriately modify their assessments and interventions (Ravi Rastgi, et al., 2022).

Reference:

- Badghish M, Sabbahi M, Bettar F O, Abdilahi A. Knee pain might originate from your lower back. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2015.03.236.

- Cannon DE, Dillingham TR, Miao H, et al. Musculoskeletal disorders in referrals for suspected cervical radiculopathy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88:1256–1259.

- Friis ML, Gulliksen CG, Rasnussen P, Husby J: Pain and spinal root compression. Acta Neurochir 39:241, 1977.

- Gunn C, Milbrandt WE. Tennis elbow and the cervical spine. Can Med Assoc J. 1976;114(9):803–809.

- Hashimoto S, Hirokado M, Takasaki H. The most common classification in the mechanical diagnosis and therapy for patients with a primary complaint of non-acute knee pain was spinal derangement: a retrospective chart review. J Man Manip Ther. 2019;27(1):33–42.

- Heidar Abady A, Rosedale R, Chesworth BM, et al. Application of the McKenzie system of mechanical diagnosis and therapy (MDT) in patients with shoulder pain; a prospective longitudinal study. J Man Manip Ther. 2017;25(5):235–243.

- Jang JS, An SH, Lee SH: Clinical analysis of extraforaminal entrapment of L5 in the lumbosacral spine. J Korean Neurosurg.Soc 36:383-387, 2004.

- Karel YHJM, GGM S-P, Thoomes-de Graaf M, et al. Physiotherapy for patients with shoulder pain in primary care: a descriptive study of diagnostic- and therapeutic management. Physiother. 2017;103 (4):369–378.

- Kim SE, Lee SH, lee DY, Lee HS:Atypical clinical presentation of lumbosacral extraforaminal disc herniation- two case reports. Kor J Spine 3:171-174, 2006.

- May S, Rosedale R. An international survey of the comprehensiveness of the McKenzie classification system and the proportions of classifications and directional preferences in patients with spinal pain. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2019;39:10–15.

- Pheasant S. Cervical contribution to functional shoulder impingement: two case reports.Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2016;11(6):980–991.

- Rastogi R, Rosedale R, Kidd J, Lynch G, Supp G, Robbins SM. Exploring indicators of extremity pain of spinal source as identified by Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy (MDT): a secondary analysis of a prospective cohort study. J Man Manip Ther. 2022 Jun;30(3):172-179. doi:10.1080/10669817.2022.2030625. Epub 2022 Jan 25. PMID: 35076353; PMCID: PMC9255208.

- Rosedale R, Rastogi R, Kidd J, Lynch G, Supp G, Robbins SM. A study exploring the prevalence of Extremity Pain of Spinal Source (EXPOSS). J Man Manip Ther. 2020 Sep;28(4):222-230. doi: 10.1080/10669817.2019.1661706. Epub 2019 Sep 2. PMID: 31476129; PMCID: PMC8550529.

- Walker T, Salt E, Lynch G, et al. Screening of the cervical spine in subacromial shoulder pain:A systematic review. Shoulder Elb. 2018 September 20. DOI:10.1177/1758573218798023. 21.

- Wisneski RJ, Garfin SR, Rothman RH, Lutz GE: Lumbar disc disease, in Herkowitz HN, Garfin SR, Balderston RA, Eismont FJ, Bell GR, Wiesel SW(eds): The Spine. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1999, pp613-679.