Introduction

The increasing reduction and elimination of distal pain in response to therapeutic loading procedures is referred to as centralization. During the decrease of a derangement, centralization occurs. This blog provides a full discussion of the phenomenon as well as an overview of its features.

Definition

Centralisation is the process by which the distal pain coming from the spine is gradually eliminated from distal to proximal. This occurs as a result of a specific repeated movement and/or sustained position, and the shift in location is maintained over time until all pain is eliminated. The central pain often increases significantly when the discomfort centralises. If just spinal pain is present, it shifts from a wider to a more central place and is ultimately eliminated.

Centralization refers to the elimination of distal pain as a result of clinically recommended repeated endrange movements, static endrange loading, or the maintenance of correct postural habits. Distal pain can often be relieved during the initial session, and centralization and final reduction can be accomplished during the subsequent follow up sessions. On the other hand, if an early examination reveals that a specific loading technique is having a centralising effect, which, if pursued over a longer time period, it may result in the elimination of distal symptoms and the progression of centralization phenomena.

Only in derangement syndrome can the centralization phenomenon occur (McKenzie 1981, 1990). Reduction describes the process of gradually lessening the abnormality. During this phase, clinical and mechanical presentations steadily improve, resulting in centralization and mobility restoration. The processes of reduction and centralization are inextricably linked and occur concurrently. When the derangement is completely resolved, discomfort disappears and full-range, pain-free movement is restored. However, the progression of the decrease in symptoms is quite variable. Some reductions are stable for a short period of time with little application of loading methods, whereas others require careful application of loading strategies over a longer period of time to achieve and maintain a decrease. Some reductions are so fragile that a simple change in loading causes them to re-derangement. The derangement may be lessened on occasion, but pain on end-range movement, which may be limited, persists due to tissue dysfunction.

Distal discomfort is eliminated during the deployment of loading tactics by centralising. The discomfort is being centralised, but this will only be proven until the distal pain has been eliminated.

Centralised indicates the patient’s status when all distal pain has been eliminated as a result of the adoption of the appropriate loading tactics, and the patient now only suffers back discomfort. The core back ache will then gradually fade and disappear.

Centralization is associated with the pain arising from the intervertebral disc (Donelson et al 1990 and 1997, Laslett et al 2005). Therefore, the pain that is due to the deployment of loading techniques might either be steady or unstable. Stable symptomatic improvement as a result of end-range loading suggests the stable nature of the derangement reduction and, in general, implies a promising prognosis. For example, the centralization of symptoms that develop during standing loading is usually stable.

Unstable reduction may signal that a positive prognosis can be reached over time if rigorous management is used; nevertheless, it typically signifies a derangement that is not susceptible to long-term reduction, and the prognosis in these cases is bad. Over a few days of testing, it is usually possible to assess whether or not decreased stability and a long-term centralising impact are being achieved. Pain relief achieved spontaneously by lying down is not an indicator that the abnormality has been alleviated. In this situation, pain has subsided due to the removal of compressive loading and will return with the return of weight-bearing. It is not reasonable to consider that centralization or reduction has occurred in this case.

Definition of Peripheralisation / Peripheralising / Peripheralised

Peripheralization is the process by which the proximal symptoms starting in the spine move in a proximal-to-distal direction. This occurs as a result of a specific recurrent movement and/or protracted position, and the change in location of symptoms persists over time. This may also be linked to a deterioration in neurological status.

Peripheralizing refers to the production of distal symptoms during the application of loading tactics. Symptoms are getting peripheralized; however, this will not be established until the distal symptoms persist.

Peripheralized means that the patient reports that the distal symptoms that were developed are still present as a result of the incorrect loading tactics used.

A quick recap

Centralisation:

Peripheralisation:

If pain has centralised, the prognosis is typically good. For patients whose discomfort has extended below the knee and did not go away, the symptoms have worsened rather than alleviated by these techniques. In this situation, the repeated motions in the sagittal and frontal planes have aggravated or generated referred pain and neurological problems. The mechanical therapy did not help these patients.

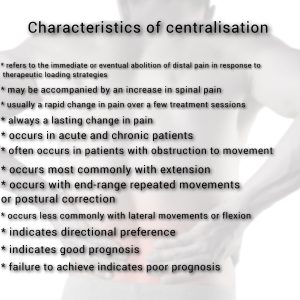

Centralization characteristics

The prognostic relevance of centralization will become clear once it is discovered that motions that cause pain to centralise are therapeutic and result in a positive outcome. Movements that result in centralization also point in the direction of any mobilising or manipulation methods that should be utilised when an increase in force is required due to incomplete or partial responses to self-treatment exercises. Similarly, it becomes evident that motions that induced symptoms on the periphery were undesirable and hence should not be progressed. Centralization is more typically seen in patients who also have significant impediments to full range of extension.

Although many patients with back discomfort get centralization when performing extension exercises from a prone lying position, others, if indicated during mechanical evaluation, must practice extension from a prone hips off-centre position. Some patients respond to lateral movements, while others must repeat flexion motions to achieve pain centralization. Patients typically display this directional preference, where one direction helps reduce symptoms while the opposite worsens them.

Literature on centralization

During repeated movement tests, centralization phenomena has been commonly identified in the literature (Donelson et al. 1990, 1991, 1997; Williams et al. 1991; Long 1995; Sufka et al. 1998; Erhard et al. 1994; Karas et al. 1997; Delitto et al. 1993; Kilby et al. 1990; Kopp et al. 1986; Werneke et al. 1999; Werneke and Hart 2000, 2001). This has occurred in half to three-quarters of the patient groups studied. In both acute and chronic back pain populations, centralization has been linked to improved outcomes (Donelson et al., 1990; Sufka et al., 1998; Long, 1995; Rath and Rath, 1996). When compared to patients whose symptoms did not centralise, centralization was linked with lower functional impairment ratings and higher rates of return to work (Werneke et al., 1999; Sufka et al., 1998; Karas et al., 1997). Centralization is strongly associated with greater improvements in pain severity and perceived functional limitations, but it is also strongly associated with poor overall response (Donelson et al., 1990; Karas et al., 1997; Werneke et al., 1999; Werneke and Hart, 2000).

To summarise, centralization can occur or begin to occur on the first day; nevertheless, in some cases, it takes many weeks. It might happen during therapy sessions as well as gradually in between sessions. The main differential, however, is between those who fail to centralise at all and those who may undergo centralization quickly or slowly. Outcomes are likely to be positive in those experiencing centralization—the elimination of distal symptoms that last. Failure to change symptoms after a full trial of up to seven therapy sessions is associated with a bad outcome.

Assessment of symptomatic response reliability

Because the phenomenon of centralization is entirely predicated on the patient’s assessment of pain location and behaviour, it is critical to make sure that this subjective reaction has been examined properly.

The Kappa value is a numerical expression of tester agreement that attempts to eliminate the impact of chance. If multiple clinicians agree on the presence of centralization in an individual, the kappa value has been found to be good to excellent, with rates of agreement ranging from 90% to 100% (Sufka et al., 1998; Werneke et al., 1999). In one study involving eighty physical therapists and students who were evaluated on their ability to judge pain changes during movement from a video, the rate of agreement was 88% and the Kappa value was 0.79 (Fritz et al., 2000a). These investigations have demonstrated that pain judgements and pain behaviour on mobility can be reliably examined (Spratt et al., 1990; Donahue et al., 1996; Kilby et al., 1990; McCombe et al., 1989; Strender et al., 1997). Pain response tests are invariably more reliable than visual or palpatory queuing testing (Donahue et al., 1996; Kilby et al., 1990; Strender et al., 1997; Potter and Rothstein, 1985).

Considering the disadvantages of imaging and other diagnostic procedures in identifying the underlying condition, pain and, more specifically, its location could be used as a reflection of the character of that underlying disorder (Donelson et al. 1991).

Centralization in Cervical spine

Werneke et al. (1999) documented the symptoms of 289 individuals, 66 (23%) of whom had neck pain. Centralization was precisely defined as a distinct abolition during mechanical evaluation that remained better and improved progressively at each session. Another group, labelled ‘partial reduction,’ showed incremental improvement over time, but this was not always progressive or obviously related to the therapy session. Similar percentages of patients with neck and back pain showed centralization (25% and 31%, respectively) and partial reduction (46% and 44%, respectively). Because there were no significant variations in outcome by pain site, patients with back and neck pain were studied together. Centralizers made four fewer visits on average than the partial reduction and non-centralization groups (eight). However, there was no statistically significant difference in pain or functional outcome between the centralization and partial reduction groups, both of which were significantly better than the non-centralization group.

Conclusions

- The centralization phenomenon refers to the long-term eradication of distal, referred symptoms in response to therapeutic loading.

- The phenomenon of centralization is used as a positive prognostic sign.

- Failure to change the location of distal symptoms is connected with poor outcomes.

References

- Delillo A, Cibulka MT, Erhard RE, Bowling RW, Tenhula JA (1993) Evidcnce for use of an extension-mobilisation category in acute low back syndrome: a prescriptive validation pilot study. Physical Therapy 73.216-228.

- Donelson R, Silva G, Murphy K (1990). Centralization phenomenon. Its usefulness in evaluating and treating referred pain. Spine 15.211-213.

- Donelson R, Grant W, Kamps C, Medcalf R (1991). Pain response to sagital end-range spinal motion. A prospective, randomised, multicentered trial Spine 16. 5206-5212.

- Donelson R, Aprill C, Medcalf R, Grant W (1997). A prospective study of centralization of lumbar and referred pain. A predictor of symptomatic discs and annular competence. Spine 22. 1115-1122.

- Donahue MS, Riddle DL, Sullivan MS (1996) Intenester reliability of a modified version of McKenzie’s lateral shift assessments obtained on patients with low back pain. Physical Therapy 76.706-726.

- Erhard RE, Delillo A, Cibulka MT (1994). Relative effectiveness of an extension program and a combined program of manipulation and flexion and extension exercises in patients with acute low back syndrome. Physical Therapy 74.1093-1100.

- FritzJM, DelillO A, Vignovic M, Busse RG (2000a). Interrater reliability of judgements of the centralization phenomenon and status change during movement testing in patients with low back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 81.57-61.

- Karas R, Mcintosh G, Hall H, Wi lson L, Melles T (1997). The relationship between nonorganic signs and celllralization of symptoms in the prediction of return to work for patients with low back pain. Physical Therapy 77.354-360.

- Kilby J, Stigant M, Roberts A (1990) The reliability of back pain assessment by physiotherapists, using a ‘McKenzie algorithm’. Physiot herapy 76.579-583.

- Kopp JR, Alexander AH, Turocy RH , Levrini MG, Lichtman OM (1986). The use of lumbar extension in the evaluation and treatment of patients with acute herniated nucleus pulposus. A preliminary report. Clin Onhop & Rei Res 202:211-218.

- Long AL (1995). The centralization phenomenon. Its usefulness as a predictor of outcome in conservative treatment of chronic low back pain (a pilot study). Spine 20.2513-2521.

- McCombe PF, Fairbank J CT, Cockersole BC, Pynsent PB (1989). Reproducibility of physical signs in low-back pain. Spine 14.9.908-918.

- Potter NA, Rothstein JM (1985). Intertester reliability for selected cl inical tests of the sacroiliac joint. Physical Therapy 65.11.1671-1675.

- Rath W, RathJD (1996). Outcome assessment in clinical practice. McKenzie Institute (USA) Journal 4.9-16.

- Spratt KF, Lehmann TR, Weinstein JN, Sayre HA (1990). A new approach to the low-back physical examination. Behavioural assessment of mechanical signs.Spine 15.96-102.

- Sufka A, Hauger B, Trenary M et al. (1998). Centralization of low back pain and perceived functional outcome.JOSPT 27.205-212.

- Strender LE, Sjoblom A, Sundell K, Ludwig R, Taube A (1997). Interexaminer reliability in physical examinations of patients with low back pain. Spine 22.814-820.

- Werneke M, Hart DL, Cook D (1999). A descriptive study of the centralization phenomenon. Spine 24.676-683.

- Werneke M, Hart DL (2000). Role of the centralization phenomenon as a prognostic factor for chronic pain or disability. JOSPT 30.1. Abstract. A33. PL96.

- Werneke M, Hart DL (2001). Centralization phenomenon as a prognostic factor for chronic low back pain and disability. Spine 26.758-765 .

- Williams MM, Hawley JA, McKenzie RA, van Wijmen PM (1991). A comparison of the effects of two sitting postures on back and referred pain. Spine 16.1185-1191.

Good summary. Well done. You might mention that cventralisation is linked to pain proven to be arising from the intervertebral disc (Donelson et al 1990 and 1997), and demostrable high specificity to controlled provocation discography as reference standard for doscogenic pain (Laslett et al 2005)

Thanks Dr. Laslett, appreciated.

You’re absolutely right. Centralization is linked to the pain arising from the disc. I think that makes the response to loading strategies either stable or unstable.

I have cited your work in my previous write ups as well. Check them out! I’d be happy to hear your thoughts!

https://www.orthopaedicmanipulation.com/part-4-evidence-behind-mckenzie-method-of-mechanical-diagnosis-and-therapy/

https://www.orthopaedicmanipulation.com/discogenic-back-pain-part-1/