Importance of agreement between clinicians while making a diagnosis

Agreement between clinicians is an important factor in the context of making a diagnosis. When multiple clinicians agree on a diagnosis or the interpretation of diagnostic data, it can enhance the reliability of the diagnostic process, improve patient outcomes, and provide a more robust framework for decision-making.

Let’s explore how clinician agreement plays a role in this context:

1. Enhancing Diagnostic Accuracy and Consistency

Reduction of Diagnostic Errors: Agreement between clinicians can help reduce diagnostic errors. When multiple clinicians independently arrive at the same diagnosis or similar probability estimates for potential conditions, it increases confidence in the accuracy of the diagnosis. This consensus can act as a check against individual errors or biases, such as anchoring or premature closure, which might lead a single clinician to focus too narrowly on a particular diagnosis.

Standardization of Diagnostic Practices: Agreement on the interpretation of clinical findings, symptoms, and diagnostic test results helps standardize practices across different clinicians. This standardization is particularly important in settings like emergency departments or multidisciplinary teams, where consistent diagnostic approaches are necessary to ensure continuity of care.

2. Improving Probabilistic Reasoning and Decision-Making

Refining Probability Estimates: When clinicians collaborate and discuss the likelihood of different diagnoses, they can refine probability estimates based on collective expertise and experience. This collaborative approach can help identify overlooked possibilities, reconsider unlikely but serious diagnoses, and recalibrate the probabilities based on a broader base of knowledge.

Facilitating Peer Review and Feedback: Agreement (or disagreement) between clinicians provides an opportunity for peer review and feedback. In cases where there is disagreement, clinicians are encouraged to discuss their reasoning, consider alternative hypotheses, and review additional data or evidence. This process not only refines diagnostic probabilities but also enhances learning and professional development.

3. Supporting Evidence-Based Practice and Clinical Guidelines

Adherence to Clinical Guidelines: Agreement among clinicians is often based on adherence to evidence-based clinical guidelines and protocols, which are developed to standardize care based on the best available evidence. When clinicians follow these guidelines, they are more likely to agree on diagnoses and management plans, ensuring consistent and high-quality care across different providers.

Validation of Clinical Guidelines: Conversely, when clinicians frequently disagree despite following guidelines, it may indicate a need to update or refine these guidelines. Continuous monitoring of clinician agreement and disagreement can inform the development of more precise and effective clinical guidelines, ultimately improving diagnostic accuracy and patient outcomes.

4. Enhancing Patient Trust and Satisfaction

Building Patient Confidence: When multiple clinicians independently arrive at the same diagnosis, it can build patient confidence in the diagnosis and the proposed treatment plan. Patients may feel more reassured when they know that their diagnosis is supported by the collective expertise of several clinicians (e.g., when patients seek a second opinion for a cancer-free diagnosis) rather than a single opinion.

Facilitating Shared Decision-Making: Agreement among clinicians can facilitate shared decision-making by presenting a unified, consistent message to patients. When clinicians are aligned in their diagnosis and management plan, it is easier to communicate this information to patients, helping them make informed decisions about their care.

5. Challenges and Limitations of Clinician Agreement

Risk of collaborative thinking: While agreement can enhance diagnostic accuracy, there is also a risk of collaborative thinking, where clinicians may conform to the opinions of others rather than critically evaluating all available data. This conformity can stifle diverse opinions, reduce the exploration of alternative diagnoses, and lead to diagnostic errors.

Potential for Bias: In some cases, clinician agreement may not necessarily indicate the correct diagnosis but rather reflect shared biases or common training backgrounds. For example, clinicians trained in the same institution may have similar diagnostic approaches and biases, which could influence their agreement on a diagnosis.

Handling Disagreements: Disagreements among clinicians, while challenging, can also be beneficial. They encourage thorough discussion and reconsideration of diagnostic probabilities, potentially uncovering missed diagnoses or new insights. However, managing these disagreements requires effective communication, respect for differing opinions, and a structured approach to resolving conflicts.

Therefore, agreement between clinicians plays a significant role in the context of making a diagnosis, via., probabilistic thinking and the hypothetico-deductive method of diagnosis. It enhances diagnostic accuracy, supports evidence-based practice, facilitates shared decision-making, and improves patient trust. However, it is also important to recognize the potential challenges and limitations, such as the risks of collaborative thinking and shared biases. By fostering a culture of collaboration, open communication, and critical thinking, healthcare teams can leverage clinician agreement to optimize diagnostic outcomes and patient care.

How to Measure Diagnostic Agreement Between Clinicians

The hypothetico-deductive diagnostic method involves collecting clinical data that serve as determinants of diagnosis, prognosis, and response to treatment. This clinical data, obtained through subjective and objective assessments, can vary significantly between clinicians. Therefore, it is crucial to collect reproducible and reliable information from patients to form accurate hypotheses and make well-informed diagnoses.

Methods such as inter-rater reliability tests, including Cohen’s kappa and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), are commonly used to quantify the extent of agreement between clinicians and identify areas where diagnostic practices may need standardization or improvement (1-3). By evaluating inter-clinician agreement, healthcare providers can improve the consistency and reliability of clinical assessments, ultimately enhancing the quality of patient care.

Here is an example of how to measure the diagnostic agreement between two clinicians following the single leg raise tests on patients with lumbar radiculopathy:

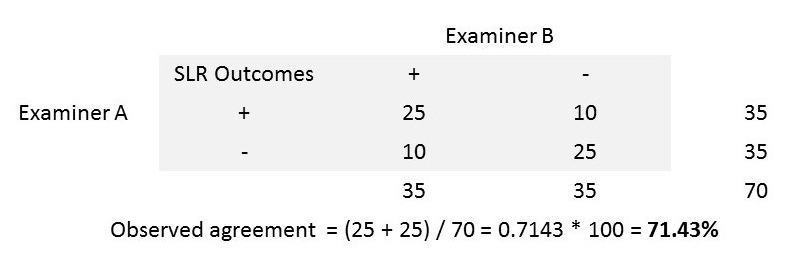

Step 1: Let us read the outcomes of the single leg raise tests from two examiners from the 2×2 table below with mock data (Figure 1) and calculate the actual agreement between them.

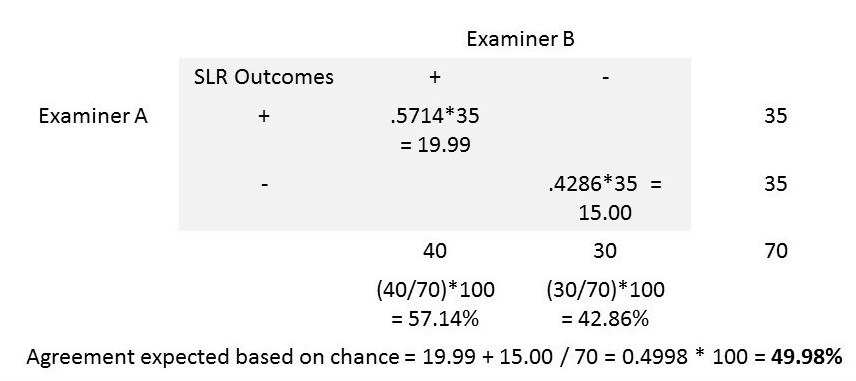

Step 2: Now, let us find if the agreement between these two examiners occurred by random chance. We can identify such random chance agreement by assuming one of the examiners was tossing a coin and making his/her decisions. Let us assume the examiner ‘B’ tossed a coin and had 40 heads (SLR +ve) and 30 tails (SLR -ve).

By random chance, we can expect 57.14% (i.e., 40/70 * 100) of the 35 SLR results reported as ‘+’ by examiner ‘A’ to be ‘+’ be examiner ‘B’ as well. We can also expect 42.86% (i.e., 30/70 * 100) of the 35 results reported as ‘-‘ by examiner ‘A’ to be ‘-‘ by examiner ‘B’ as well.

The agreement between the two examiners expected based on random chance can now be calculated as (19.99 + 15.00) / 70 = 0.4998 or 49.98%.

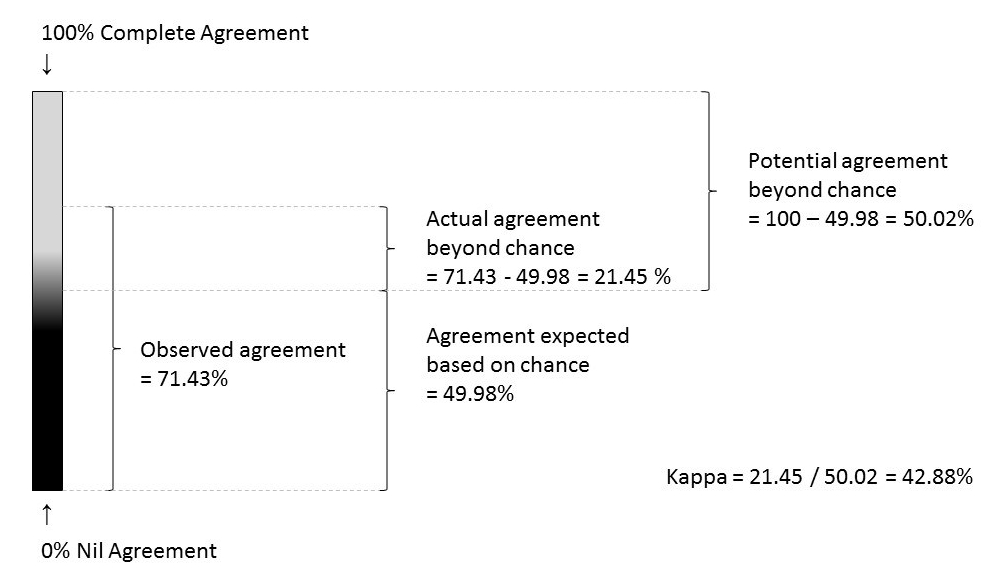

Step 3: The comparison of observed agreement (71.43% in step 1) and the agreement expected based on random chance (49.97% in step 2) will give us a clinically useful index called ‘kappa degree of agreement’ (4).

kappa = actual agreement beyond chance / potential agreement beyond chance

In the step 1, the actual agreement beyond chance = 71.43 – 49.98 = 21.45 %

In the step 2, the potential agreement beyond chance = 100 – 49.98 = 50.02 %

kappa = 21.45 / 50.02 = 0.4288

Hence, the proportion of agreement between two examiners beyond chance (kappa) was 0.43

The kappa values can be categorized for meaningful interpretation as follows:

< 0 Less than chance agreement

0.01–0.20 Slight agreement

0.21– 0.40 Fair agreement

0.41–0.60 Moderate agreement

0.61–0.80 Substantial agreement

0.81–0.99 Almost perfect agreement

Issue of Clinical Disagreement: Additionally, the extent of disagreement between the examiners is also important as it is prevalent in every step of the clinical care. For example, when a patient visits a care provider for the first time to consult about his/her knee pain, the clinician listens to the patient and documents the symptoms. The disagreement between the clinicians starts at this very first step. If the patient consults two clinicians separately on the same day, there will be differences in the clinical data collected between these two clinicians.

From this point onwards, the hypotheses generation, differential diagnoses, treatment options, referrals, follow-up care and decision on discharge from further treatment will differ (to a certain degree) between these two clinicians. As long as the care provider and the recipient are biologic beings, there will always be a certain degree of subjectiveness in our current model of health care.

The main reasons for clinical disagreement include the following:

- Biologic variation in the presenting symptoms/signs

- Biologic variation of the clinician’s sensory-motor ability to observe the presenting symptoms/signs

- The ambiguity of the presenting symptom/sign being observed

- Clinician’s biases (e.g., influence of gestalt patterns, cultural differences etc.,)

- Faulty application of clinical data collection methods (e.g., off on a wrong track during history taking)

- Clinician’s incompetence or carelessness

We can apply certain strategies to prevent or reduce the possibility of clinical disagreement. They are:

- define the observed symptoms/signs clearly

- define the technique of observation clearly

- master the technique of observation

- avoid the biases consciously

- seek for a standardized environment while performing clinical observation/tests

- seek for blinded opinions from your colleagues and corroborate your findings

- use refined, highly calibrated tools for measurement (e.g., VAS in mm)

- document your findings using standardized (between clinicians) format

Weighted kappa: The standard kappa statistic measures the degree of agreement between two clinicians but does not account for the degree of disagreement. However, the nice property of kappa statistic is that we can give different weights to the disagreements depending on the magnitude, i.e., the higher the disagreement between clinicians, the higher the weights assigned.

Warrens (5) reports that there are eight different weighting schemes available for 3 x 3 categorical tables. An appropriate weighting scheme can be chosen by considering the type of categorical scale used to measure the degree of agreement between the clinicians. The weighted kappas proposed by Cicchetti (6) and Warrens (7) can be used for dichotomous ordinal scale data. And, the linearly and quadratically weighted kappas can be used for continuous ordinal data (5).

The most commonly used and criticized one is the weighted Cohen’s kappa for nominal categories (5). The quadratically weighted kappa is also popular as it produces higher values (5). A judicious use of the weighting schemes is recommended to avoid wrong decisions in clinical practice (5).

Reference:

- Sackett, David L & Sackett, David L. Clinical epidemiology (1991). Clinical epidemiology : a basic science for clinical medicine (2nd ed). Little, Brown, Boston, MA

- Fletcher, R.H., Fletcher, S.W. and Fletcher, G.S., 2012. Clinical epidemiology: the essentials. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- McGee, S., 2012. Evidence-based physical diagnosis. Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Viera, A.J. and Garrett, J.M., 2005. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med, 37(5), pp.360-363.

- Warrens, M.J., 2013. Weighted Kappas for Tables. Journal of Probability and Statistics, 2013.

- Cicchetti, D.V., 1976. Assessing inter-rater reliability for rating scales: resolving some basic issues. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 129(5), pp.452-456.

- Warrens, M.J., 2013. Cohen’s weighted kappa with additive weights. Advances in Data Analysis and Classification, 7(1), pp.41-55.